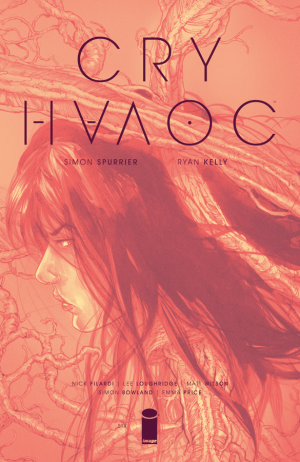

Review: Cry Havoc #6

"There's more honest magic." Much to my editor's chagrin, I'm sure, I had to take some extra time to write about the finale of Cry Havoc. For one, Spurrier put together yet another story-about-stories densely packed with personal touches and large, sweeping meta-narrative soapboxing, this time through the mouthpiece of a big black ethereal werewolf instead of a six-shootin' gorilla or the son Xavier never had but sort of had but--well, it's complicated. For another, Spurrier issued a challenge to the comic book press that hit very close to home for me. You see, I think a lot--too much, probably, because it often causes me enough anxiety-via-introspection that I cannot even write--about the best way that I, or any critic, can engage with comic books as a medium. I obsess about it, I really do, and I have a confession:

I have no fucking idea what I'm doing.

Awhile ago, I wrote an essay about how I thought we ought to approach #1 issues. Time and time again I see these reviews that latch on to two or three things that they like or did not like, and then extrapolate those feelings awkwardly into chunks of an essay that serve as nothing more than an attempt at fortune telling. I quickly realized that my favorite essays about #1 issues treated the launch issues as complete works. Surely on an emotional level you will be giving creators the benefit of the doubt and hoping for the best for the next issue, but as far as works of criticism go, a #1 issue is, in a very real sense, the totality of a given work at that time. It is a work that creators and editors and publishers chose to be the gateway into the series and, as such, you should spend your time talking about this grand entrance and not the objects you might be able to discern on the horizon beyond it. Now, of course, I understand why so many people use #1 reviews to ask perfectly valid questions about what might lie ahead; however, that doesn't make those questions terribly interesting. Still, this is all about the entry issue, the heralding issue, the ebay issue, the big fat 10 incentive variants and a fucking Pop! vinyl issue; what the shit do I do with a #3 or a #4?

Awhile ago, I wrote an essay about how I thought we ought to approach #1 issues. Time and time again I see these reviews that latch on to two or three things that they like or did not like, and then extrapolate those feelings awkwardly into chunks of an essay that serve as nothing more than an attempt at fortune telling. I quickly realized that my favorite essays about #1 issues treated the launch issues as complete works. Surely on an emotional level you will be giving creators the benefit of the doubt and hoping for the best for the next issue, but as far as works of criticism go, a #1 issue is, in a very real sense, the totality of a given work at that time. It is a work that creators and editors and publishers chose to be the gateway into the series and, as such, you should spend your time talking about this grand entrance and not the objects you might be able to discern on the horizon beyond it. Now, of course, I understand why so many people use #1 reviews to ask perfectly valid questions about what might lie ahead; however, that doesn't make those questions terribly interesting. Still, this is all about the entry issue, the heralding issue, the ebay issue, the big fat 10 incentive variants and a fucking Pop! vinyl issue; what the shit do I do with a #3 or a #4?

Do I talk about them with no reference to what's come before? Surely that's absurd: in the narrative syntax, they only have the very specific meaning they do because of what has come before. Still, this puts things in a precarious position for me as a reviewer. What if I'm not terrifically moved by the specific plot advancements of a given issue? What if all of the things that I enjoyed about the artwork were features that I had already pointed out in my review of the previous single issue? Still, when the writing is original enough (as it is in this book) and the art is varied (and, frankly, awesome, as it is in this book), there will be enough instances wherein a confluence of cool shit occurs and I can jump up and down and point and say "OMG did you see what happened here?"

And this is the point at which we're all on a different page on the reviewing side. I mean--sorry, I hate to throw people under the bus--but even if you go look at reviews of the #6 issue of this series, you still can find at least one reviewer framing his review of this comic in terms of the as-yet-to-exist future of this series. And this is where Spurrier's analogy about paper airplanes goes exactly right. Not only do we not care about the landing, many reviewers take it upon themselves to ignore the flight path of the metaphorical vessel altogether in favor of discussing how it might land and which trajectory it ought to have taken. I am guilty of all of these things. And that's why I often don't write about comics midstream. Because I think the best way for us to do our jobs is to stay aware, holistically, of the work, but mainly to freeze it at that point in time and take the opportunity to poke it and prod it and share the results. That can be, and often is, daunting when you aren't yet at the end.

A review of a #3 issue should be a review of a #3 issue: it should be answering questions that were raised through your experience of those 24 or 32 or however-many pages. Fuck what you think about what might happen next issue: if it remains to be seen then it remains to be seen. For all you know the whole thing will go up in smoke the next issue. Consider Satoshi Kon's unfinished manga, OPUS. Reviewing OPUS as it was published, before his tragic death, versus reviewing it now, in retrospect, considering it as a never-to-be-finished work are distinctly different from a critical perspective.

Context matters. If you want to review a single issue of a comic as if it is a chapter in an already-published TPB that you simply haven't read yet, then wait for the TPB to come out. If you want to review the fourth issue of a six-part mini the week it comes out, you better goddamn well roll up your sleeves and tell me all about that work. Your criticism has a timestamp on it just like the work itself. Even reviewing a final issue, as I'm about to do (or should already be doing, shout out to Dustin for letting me write all this) is distinctly different than reviewing a collected trade upon its release: one of them should spend a little more time talking about the last issue in particular, even though both will inevitably have to look back on what came before. Hopefully you can guess which is which.

Context matters. If you want to review a single issue of a comic as if it is a chapter in an already-published TPB that you simply haven't read yet, then wait for the TPB to come out. If you want to review the fourth issue of a six-part mini the week it comes out, you better goddamn well roll up your sleeves and tell me all about that work. Your criticism has a timestamp on it just like the work itself. Even reviewing a final issue, as I'm about to do (or should already be doing, shout out to Dustin for letting me write all this) is distinctly different than reviewing a collected trade upon its release: one of them should spend a little more time talking about the last issue in particular, even though both will inevitably have to look back on what came before. Hopefully you can guess which is which.

*Deep breath*. Are we all still on board?

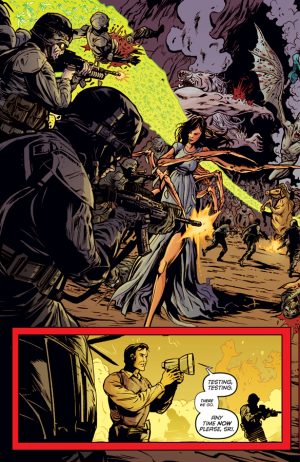

When I started Cry Havoc, I had a lot of ideas about where the series might go. One of my thoughts was that Louise was not, in fact, a werewolf at all, and that we would later discover that all of these people were just severely mentally jacked up and this was all just a very visually interesting way of telling that story. I was, obviously, extremely wrong (whether you think there's still some space for a metaphor there is up to you): Spurrier uses Kelly's surreal, brutal monster designs to double-down in this final chapter. And that, ultimately, is a really great way to understand what this story was about. Cry Havoc is a book which decisively says, if I may summarize, "Stow your fucking allegories for a minute." Our mythologies and religions and stories are not things to be explained away by our mental conditions, by evolution, or by historical circumstance: these things are very real features of our world. Whether or not you are comfortable stretching your definition of real to include unicorns or werewolves or the Penanggalan, these things clearly do exist in some way that is robust enough to scare us, to thrill us, or to inspire us. The human impulse to justify, to explain away, and to synthesize is one that is not effectively aimed towards these fictional features of our world. Rather, Spurrier thinks we are in the very hard position of Louise: we must accept that as humans we are in this weird position of having to constantly enter our collective thoughtspace and mediate between the practical and the mythological. We cannot shove it off, we cannot ignore it, we cannot put it all in a pot and try to boil it down into easily digestible metaphors.

You can tell your friend all you like about how much you think the Bible is great if you don't take it literally, but he will still believe in angels and saints as being very real features of the world. You will not convince him or billions upon billions of others otherwise. You cannot ignore them as real, complete individuals. Even if you consider yourself this hyper-rational modern humanist, you must co-exist with monotheists, with people who are afraid of clowns and ghosts, and even with people who simply hold sacred the rich traditions of their ancestors. The Zeitgeist is not one-size-fits-all. It never will be. If you want to be a human among humans, you must face both ways without getting lost in either. You must face the public as a citizen and you must face your fellow citizens as believers in all sorts of weird fictions. Even in the case that you don't fancy yourself a pluralist, the people and the stories are all still out there.

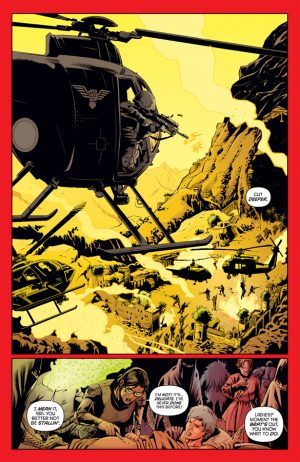

All of that brings me around to just how in sync this whole creative team was throughout this book, and it's on complete showcase in the final chapter. If Spurrier finds something particularly cool, you can tell so in the appendix. The Penanggalan was teased awhile ago, and he made sure to take some extra time in the back of the final issue to unpack this Malaysian vampire's historical baggage. Kelly's spread for the Penanggalan stands out even among the other monster spreads he's gotten to do in the series. It's one thing to draw all of the "cords of viscera" springing out from the Penanggalan: it's another thing to have it all composed so thoughtfully. The spread is shocking and brutal, but it also reads well. Kelly's pencils have in them this trend towards controlled chaos. Even when he unleashes the beast (literally), there's a sense that his hand is still guiding the reader in a measured way.

All of that brings me around to just how in sync this whole creative team was throughout this book, and it's on complete showcase in the final chapter. If Spurrier finds something particularly cool, you can tell so in the appendix. The Penanggalan was teased awhile ago, and he made sure to take some extra time in the back of the final issue to unpack this Malaysian vampire's historical baggage. Kelly's spread for the Penanggalan stands out even among the other monster spreads he's gotten to do in the series. It's one thing to draw all of the "cords of viscera" springing out from the Penanggalan: it's another thing to have it all composed so thoughtfully. The spread is shocking and brutal, but it also reads well. Kelly's pencils have in them this trend towards controlled chaos. Even when he unleashes the beast (literally), there's a sense that his hand is still guiding the reader in a measured way.

And that all just sits on top of the fact that Kelly was built to drawn this story. When he draws a monster, compared to how he is so carefully presenting the rest of the real world, there is a palpable tension as a reader as to what's real and what's not. The tension between the fictional and the real that comprises the very soul of this story is one that Kelly was visually presenting on the page from the very start. Further, it's a feeling that is amplified to the nth degree by choice further govern the tone with the alternating colorists.

Letterer Simon Bowland puts in his best work yet, having to guide the reader's eye through critical monologues, sometimes on pages with nothing but a handful of implied panel borders. Even though Spurrier really kept a lot of his wording as tight as possible, some sequences couldn't help but border on verbose given the amount of information that needed conveying, and Bowland kept things moving. This was especially critical in this final issue where more than ever the alternating rhythms of London and The Red Place and Afghanistan demanded an attention to layout and timing moreso than where the eye needed to be at any given time. Bowland never distracts the reader, even at critical junctures where a switch in the lettering style is the main feature of a given narrative beat.

Never more than this issue has the colorist trio of Filardi, Loughridge, and Wilson had to juxtapose their work, alternating within the spans of single pages. This issue leveraged their differences to differentiate not only time, but space (as time only arbitrarily correlated to those spaces earlier in the story), as well as even metaphorical space in some cases. The result is a triumph of Price's design work on top of the stellar color work. My only worry with the first few issues was the rigidity of the page layouts and accompanying panel border colors. It's the breaking of that convention that makes this final issue feel so fluid and satisfying. Naturally, some of Kelly's simplest pages (if you can call any of these pages that) become some of his best with these guys wielding the colors.

Despite Cry Havoc being a work that stands, in many ways, as firmly anti-allegory, it is, of course, allegorical in all sorts of ways. There's so much more to say about this work in terms of sexuality, in terms of mental illness, in terms of how we think about war, especially in terms of how we've gotten involved in modern conflicts; this is a dense work, full of concepts, many of which are fully-formed and all of which have beating hearts. The art is part-and-parcel with unpacking these concepts, and just as there are things I didn't get to say about war, there are things I didn't get to say about how particularly excellent the color work is in several instances.

Despite Cry Havoc being a work that stands, in many ways, as firmly anti-allegory, it is, of course, allegorical in all sorts of ways. There's so much more to say about this work in terms of sexuality, in terms of mental illness, in terms of how we think about war, especially in terms of how we've gotten involved in modern conflicts; this is a dense work, full of concepts, many of which are fully-formed and all of which have beating hearts. The art is part-and-parcel with unpacking these concepts, and just as there are things I didn't get to say about war, there are things I didn't get to say about how particularly excellent the color work is in several instances.

But I'm not here to write about it all, I'm just not. There's a more honest magic for us reviewers, and it's built on a necessity to bring to the table the things about a work that grabbed us, individually, and that we feel best equipped to explain while exploring our limits as both readers and writers. This requires a pretty hardcore willingness to set aside practical realities like the issue number whenever we can, and to dig right into the work, being (annoyingly) measured in how we sort through our thoughts and reactions. It all requires the oldest magic there is: fucking work.

I'd like for creators to take something away from Cry Havoc too: stop "trojan-ing" your goddamn readers. Don't give us a story in order to then step in and fill your own mythical space with saran gas by treating it all like a game: you are putting your stories into the real world. You are adding wonderful, and sometimes not-so-wonderful, branches to our collective consciousness. But then, at the first sign of trouble, you disavow your stories of any significance, attempting to pass your contributions off like cysts you can just pop with passive aggressive tweets aimed at people who are, unlike you, working their asses off trying to navigate the tricky DMZ between reality and fiction.

Through all of this philosophizing and self-reflection and advice-columning and Spurrier's own incitement of this both in his challenge to the press and in his appendices throughout these issues, Cry Havoc can feel a little academic (goodness knows the length of this review alone would make it admissable in to several reputable academic journals). But I think that's probably off-base: Cry Havoc is a work that makes you ask what you want from the stories in your life. It is a story that prepares you and then places you in a situation to face how you and the people around you treat the untouchable or unverifiable features of the world. Either you take up the challenge in earnest, or wake up one morning to find out you're an insufferable shit who knows a dozen movie casting factoids but can't remember the last time he got lost between the panels of a comic book.

[su_box title="Score: 5/5" style="glass" box_color="#8955ab" radius="6"]

[/su_box]