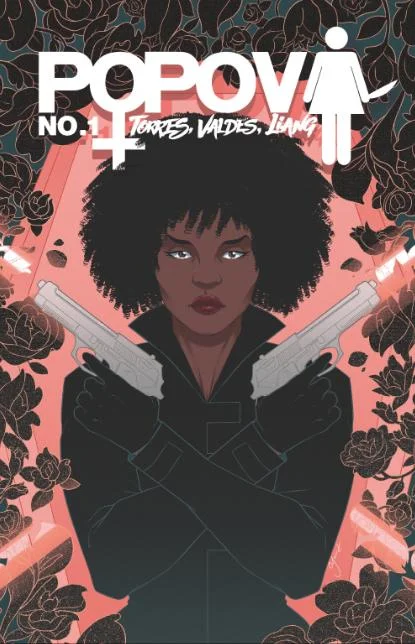

Review: Popova #1

By Ben Boruff

Writers Dre Torres and Alex Valdes are not afraid of difficult tasks. The two creators of Popova, a Tarantino-style comic that "explores the idea of reversing society's gender stereotypes by depicting women in the role of the aggressor," also created a documentary called The Last Taino. Here is the documentary's description as noted on the film's Indiegogo page:

"According to most historical accounts the Taínos, native people of Caribbean islands like Puerto Rico, Hispañola, and Cuba, became extinct shortly after the arrival of the Spaniards in 1492. After hearing a rumor about the existence of a surviving tribe in Guantanamo, Cuba, filmmakers Dre Torres and Tony Cortes travel to the communist country to find out the truth. What results is a dangerous covert voyage through the highly restricted mountains of Yateras despite the orders of Cuban military officials."

Creating a documentary like The Last Taino is a difficult task. Writing a comic like Popova may be even harder.

Popova exists in a time when misogynistic leaders dismiss the rights of women and boast about assault, and I find it difficult to separate this comic from modern sociopolitical dialogues about sex and gender. And I do not think that Popova's creators want me to separate this comic from modern political discourse. Popova is meant to help readers analyze their realities. Dre Torres, Alex Valdes, and artist Yasmin Liang have, as Shakespeare's Hamlet says, "set you up a glass / Where you may see the inmost part of you."

Popova is a justifiably angry response to real-life sexism. The black-and-white panels are filled with violence, and much of that aggression is targeted at men. When Romantic-era poet William Blake wanted to highlight the abhorrent living conditions of child workers, he wrote poems that contain heartbreaking depictions of young chimney sweepers—"A little black thing among the snow, / Crying 'weep! 'weep!' in notes of woe!"—in an attempt to mold empathy from discomfort, and reading Popova as a flipped version of real-life hostility serves a similar purpose. This comic is designed to unnerve. Subversive art forces us to question our contentment with the status quo. Popova challenges long-held shibboleths about different genders, and it does so without mercy for those who subscribe to prejudiced traditions. For some of Popova's characters, the desire to challenge oppression takes the form of a "thirst for justice, retribution, and blood."

The comic's female protagonist, however, does not share this thirst, and that complexity is what makes Popova such a difficult narrative. This comic's premise is not entirely original—Kill Bill, The Hunger Games, and Mad Max: Fury Road all feature female protagonists who fight violently against patriarchal oppression—but Popova's commentaries are uniquely multifaceted. One character is a "guilty until proven innocent" perpetrator of domestic violence, and another character is a "devout feminist" who threatens to kill a man ("filthy mutt") in front of his girlfriend. Popova is about more than gender stereotypes: it is about violence, sexuality, grief, cruelty, bureaucracy, and perceptions of feminism. Though I applaud Popova's acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of complex issues, I fear that unchecked intricacy will muddy the comic's important social commentary.

According to the Miami New Times, the inspiration for Popova came from the life of Madame Alexe Popova, a Russian serial killer from the late 1800s who supposedly murdered over 300 men. Madame Popova wished to liberate women from their ruthless husbands, and some of Popova's characters share Alexe's motivations. That said, I feel that the first issue of Popova connects more with the story of Elena Ivanovna Popova, a character in Anton Chekhov's The Bear. Chekhov's Popova feels both hate toward some men—"You're a boor! A coarse bear! A Bourbon! A monster!"—and love toward one man—"What grace there was in his figure when he pulled at the reins with all his strength!"—and this type of ambivalence is what makes Scarlet Rose, Popova's protagonist, such an intriguing character.

Ultimately, it doesn't matter whether you prefer Madame Alexe Popova or Elena Ivanovna Popova. This story isn't about either of them: it is about Scarlet Rose. And Scarlet Rose is a badass, Trinity-esque hero who hates bullshit.

I am excited to see what she does in the second issue.

Score: 4/5

Popova #1

Writer: Dre Torres and Alex Valdes

Artist: Yasmin Liang

Publisher: Self-published