Review: White Collar

Even as a historian, I’ve always hated the expression “those who ignore the past are doomed to repeat it.” It’s a silly way of oversimplifying history’s relevance to the present by suggesting that it offers some kind of easy map we can use to avoid catastrophe. If life were so simple, it wouldn’t be so unpleasant in the first place. But, in reading a book like White Collar, one can also remember that studying the past can carry uncomfortable echoes to what’s going on now. At a time when income inequality is matching the heights of 1929, deregulated banks can make investment decisions that may be extraordinarily responsible without fear of oversight, and working people are once again without unions, White Collar is a discomfiting reminder that crisis can always just be around the corner.

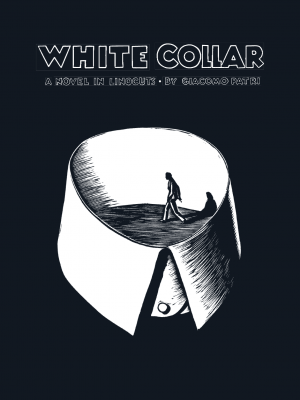

White Collar was written from 1935 to 1938 by Giacomo Patri, an Italian immigrant to the United States who settled in San Francisco. Patri worked as an advertising illustrator and newspaperman for the San Francisco Chronicle before teaching art for most of the remainder of his life. Patri was a leftist and committed union man, though he approached support for unions from an unusual angle. Crippled by polio, Patri never worked as an industrial laborer; he was a white-collar laborer for his entire life. That is the point of White Collar: it tells the story of an advertising man and his family, first forced into unemployment by the Stock Market crash, then into debt, medical crises, and finally homelessness.

How is the book told? That’s really the fascinating part: it is almost entirely wordless, with only a few simple words in the linocuts themselves. Speaking of the linocuts, this is not a typically illustrated book. Patri spent years cutting the linoleum shapes and then pressing them into paper; the result is a book of striking depth and shading. The style of illustration is typical of the 1930s, an aesthetic that’s probably better known for the 21st-century audience through Bioshock or other deliberately retro properties. It’s still strikingly experimental, which says something that the book is coming up on its eightieth birthday.

How is the book told? That’s really the fascinating part: it is almost entirely wordless, with only a few simple words in the linocuts themselves. Speaking of the linocuts, this is not a typically illustrated book. Patri spent years cutting the linoleum shapes and then pressing them into paper; the result is a book of striking depth and shading. The style of illustration is typical of the 1930s, an aesthetic that’s probably better known for the 21st-century audience through Bioshock or other deliberately retro properties. It’s still strikingly experimental, which says something that the book is coming up on its eightieth birthday.

Some of the references might be a touch over the head of the average reader. Most people know the NRA as the National Rifle Association, not as the National Recovery Administration, and a scene with NRA flags being hoisted will have lost its significance for most. Yet the really striking thing to me is to what extent the specific struggles are still so contemporary. When the man and his wife are forced to jump through hoops trying to find a doctor who will perform an abortion, it is reminiscent of the closure of abortion clinics in some states. Likewise, the debt they run up finally from a doctor drives them that much closer to bankruptcy.

Most of all, the central theme of the book is in some ways more relevant than it was when Patri was writing this. The fight to unionize was strongest in factories and mines, not for advertising illustrators and clerks. Today the industrial sector has shrunk in this country, and it’s unlikely to ever regain the size it once had. By contrast, the number of white-collar workers has grown along with workers in the service industry, and more workers are interested in unionizing as time goes on.

If the past doesn’t offer an exact guide to what we should do today, it can present parallels for our own lives. If as Peter Kuper suggests we have more in common with the men and women of the 1920s than we do with the people of the 1960s or 1970s, then we ought to consider the challenges they faced and how they responded. We need not copy them exactly in order to draw something useful from them.

[su_box title="Score: 5/5" style="glass" box_color="#8955ab" radius="6"]

White Collar Writer/Artist: Giacomo Patri Publisher: Dover Press Price: $24.95 Format: Hardcover; Print

[/su_box]