Review: Tarzan on the Planet of the Apes #2

By Patrick Larose

Tarzan on the Planet of the Apes has no right to be as good as it is.

This is a crossover comic—a crossover between two brands decades old that survive not on the content of their stories but by the power of their names. Everyone recognizes the dude in the loin cloth and when they hear “Planet of the Apes” they know there’ll be talking monkeys. It’s not supposed to matter if we love these characters or if their movies impacted us—we’re only meant to know who they are.

By all accounts, this book should have gone the way of all licensed crossovers—safe, boring but still filled with enough fan service to keep people buying. Something simplistic and retrograde enough to excuse two improbably properties in the same place but always safe enough to not risk tarnishing either name while keeping both sets of fans pleased.

This type of simplistic, bold-faced profiteering is what’s allowed the mainstream comic book industry to survive through bad writing and an audience that didn’t care about storytelling.

Tarzan on the Planet of the Apes isn’t anything of these things. Instead, we’ve been strangely gifted with a smart creative team telling a story about the impact of imperialism at the turn of the 20th century with the artwork of a pulp novel cover brought to panels.

By the start of this issue, time’s passed dramatically. Even though we’re a far from the moment when Tarzan’s last living relative slew his adoptive time-travelling-ape-father and his adoptive ape-brother Caesar watched, that moment hovers thick over everyone’s head. Tarzan’s older now, living in England while Caesar leads the remaining ape in resistance against the British slavers.

While Caesar goes to war in the jungle, Tarzan unwillingly profits from the capture and slavery of the hyper-intelligent apes. Tarzan eschews the customs and beliefs of Western society while still living in it.

He’s an adult now even if he lives with his cousin and there’s this overhanging question of why Tarzan would live with a person bent on enslaving the people who raised him and why he wouldn’t just leave. To use the money, to use the knowledge of his family’s operations to disrupt the horror’s they’re inflicting in Africa.

This issue gives him that chance as his cousin proposes they settle a peace with the Mangani apes. Tarzan sees it as an opportunity to not help his birth family but to save the people endangered by his blood kin.

Tarzan’s narrative here is vague and confusing when picked apart but feels compelling to read nonetheless. They’re dramatic conceits designed to fulfill the archetypal story of Moses and Rameses—two brothers raised together and placed at opposite sides of a war.

The emotional pathos of their opposite paths and their mirroring struggles ground and compel the narrative forward. Even if where Tarzan stands never quite makes sense, the path he goes down feels undeniably compelling as he aims to take British colonialism and curb it from the inside.

This is only heightened by the troubled leadership of Caesar, desperately trying to seek the counsel of a father who is no longer there. There’s a real weight to every mournful contemplation of his father’s journals. A man, or ape rather, from a far-flung and impossible future who’s knowledge and wisdom, was taken with him. Caesar searches these journals for an answer on taking down his human opposition but ultimately he’s searching for the comfort of someone who isn’t there.

I stated in my review of the first issue that I never expected to feel emotionally connected to a Tarzan story and that stays true here. However, I also never would have thought I’d see a Tarzan story try to have an honest conversation about the effects of colonialism.

There are conversations in here about the British disregard to alien cultures and languages, the profiteering on the death and loss of others. There’s a cost of life to their financial plundering of foreign countries and only when that cost is tipped towards their side is there even a second thought towards a peaceful negotiation. On the opposite side of the imperialism, Caesar grapples with the role of violence in resistance. Raised by pacifists, he has to become a child of war—a new type of person to lead his people in acts of violence in order to retain their freedom.

These are unexpectedly weighty topics for a comic about Tarzan or Planet of the Apes to cover and it never feels cloying or like a Saturday morning cartoon special. Yet by still wearing these licensed branding, it still feels…troubled.

When we first meet up with Tarzan in jolly old England, he’s harassed out of a tree by a police officer and brought to his family estate. Outside the great door and arches, there’s a gorilla waiting for him outside, dressed in a three-piece suit and informing him on his impatient cousin.

My initial thought when I saw this was, “Oh, cool. We’re so far in the future that the humans and the intelligent apes have started co-habituating.” That was a cute thought but the reality came on me quickly: “Oh. No. He’s a slave.”

The inescapable cultural reality is that Tarzan on the Planet of the Apes tackles British colonialism and slavery through the lens of its effect on a fictional species that share a name with a historically used racial epithet for a race of people who these things actually happened to. There’s a problem when it even comes to using Edgar Rice Burroughs’s fictionalized Africa as a backdrop for these conflicts. His Africa was a dense forest, barely even populated with any humans outside of British people and offensive stereotypes of native Africans. Using it means avoiding the effects of colonialism and slavery on the actual people who were actually affected by it and instead of steering us towards a “safer” discussion by using future-ape-people.

This is a trapping that seems to just happen by nature of repeatedly using a white-savior character written by an ill-educated racist white guy literally centuries dead. The character and this world were never really designed to tackle these things and avoiding complete reinventions leaves this standing architecture for writers to weave their story around.

My fingers are crossed that the narrative is cracked a little wider open and we get a more honest and accurate depiction of what colonialism did to these countries. The emotional pathos is here and it is fantastic but the thematic grounding risks straying away from an honest discussion. Then again, honesty might hurt the brand.

Score: 4/5

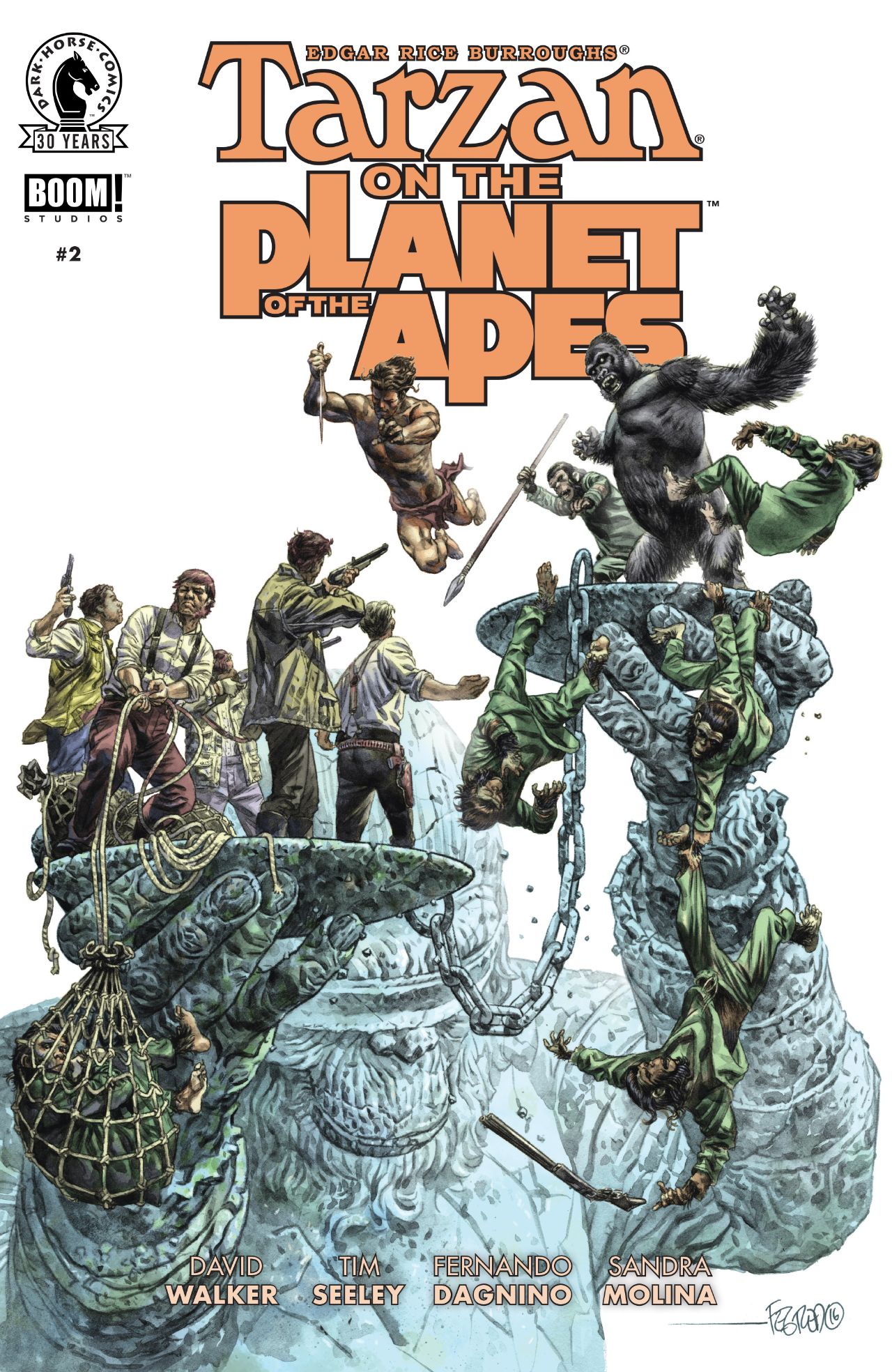

Tarzan on the Planet of the Apes #2

Writers: David Walker and Tim Seeley

Artist: Fernando Dagnino

Publisher: Dark Horse Comics

Price: $3.99

Format: Miniseries; Print/Digital